Meet Grasshopper, an underwater robot helping restore critical eelgrass meadows

The initial launch of the marine robot into the waters of Washington’s Puget Sound was a bit choppy. The tethered device, dubbed “Grasshopper,” disappeared under the flat-bottom boat from which it was gently plopped into the water.

“I think the boat went over the robot. I want to make sure that we’re not caught up by something,” said Manyu Belani, the engineer who helped build the device.

“Oh, I see it…. I don’t think I’m caught in anything,” said Nastasia Winey, the marine “roboticist” navigating the grasshopper. “I see the tape going up.”

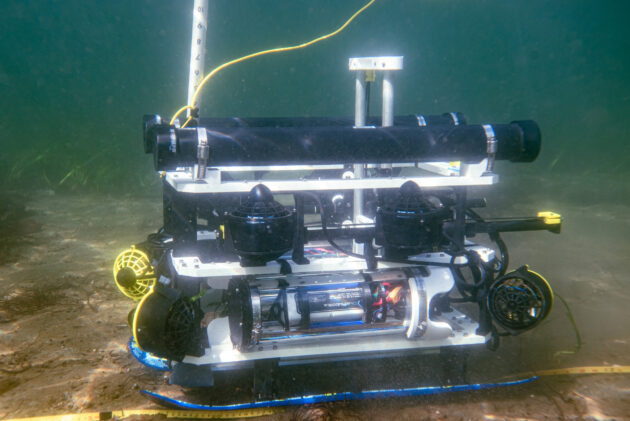

The robot emerged, its cheery yellow buoy and tether trailing behind it. Grasshopper, which is about the size of two milk crates, motored over to a bare, sandy patch in the shallow bay. Winey tracked its progress via its underwater camera. When the robot reached its target, Winey used her gaming-style controller to land it and insert two shoots of eelgrass into the sediment. It scooted forward about 10 inches and repeated the action again and then again, until 24 shoots were planted offshore of Joemma Beach State Park.

Belani and Winey are from Reefgen, a startup that’s building robots to reverse the degradation of marine ecosystems. The San Francisco company is partnering with the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to field test its new device.

“This is about restoration, and it’s about using new technologies for us to actually restore this habitat,” said Washington Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz, who donned a wet suit on Monday morning to observe the effort up close.

“We see people planting trees all the time,” she said. “It’s a big movement, especially with climate [change], but I don’t know how many people have actually seen the planting of kelp and eelgrass beds.”

Worldwide, seagrass meadows and kelp forests are disappearing from the nearshore. In Washington, eelgrass has vanished from key areas around the San Juan Islands and in certain bays and inlets in Puget Sound. State leaders two years ago approved a program to conserve and restore a minimum of 10,000 acres of kelp and eelgrass by 2040.

The algae and plants play essential roles in marine ecosystems. In the Pacific Northwest, eelgrass provides refuge for baby salmon migrating out to sea, filters the water and stabilize shorelines, and silvery herring deposit their eggs on its blades. There are roughly 50,000 acres of eelgrass in the Sound, but water pollution, higher temperatures, dredging and disease kills the plants.

For years, state experts have been monitoring the flora and working to restore it.

“I see great potential in having another method to get plants in the ground,” Jeff Gaeckle, co-leader of DNR’s Nearshore Habitat Program.

The seagrass ecologist said he has limited resources for recovering the shoreline ecosystem. Scuba divers are expensive and planting operations need to move quickly to take advantage of low-tide conditions.

Outfitted in a wetsuit, mask and snorkel on a partly sunny morning, Gaeckle got in the water at Joemma Beach to harvest shoots from a dense patch of eelgrass. He placed them in a mesh bag and swam them over to the Reefgen crew to prep for replanting in a underwater bald spot.

The team tucked the roots of the grass into spiked, metal clips that anchor them in the ground. The spikes secure the plants against waves and currents so their roots and rhizomes can grow and spread. Over time the metal rusts and the spikes disappear. They loaded the robot with 12 spikes holding two plants each.

Reefgen began its restoration work in tropical ecosystems. It developed robots that can drill small holes into dead coral reefs and insert plugs of live coral. It’s now also working on eelgrass, which it plants as seeds and shoots. It’s establishing a nursery for growing seagrass for replanting. The startup has been testing and fine tuning its technology in the San Juans, as well in California, the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

“If we think globally, the scale of habitat loss is so massive that it’s unlikely we’ll be able to address it and restore tens of thousands of acres manually,” said Reefgen CEO Chris Oakes. “And so we’re really looking at, how do we introduce technology as a force multiplier?”

The Grasshopper robot deployed in Puget Sound is so new that the team calls it “version zero.” Currently, it’s not faster than doing the shoot restoration by hand — though it is more efficient at dispersing seagrass seeds. Plans are already in the works for new devices that can carry many more plants and use spikes that will be quicker to load with shoots.

The robots are built from a combination of off-the-shelf parts and pieces made with 3D printers. Grasshopper is powered by a battery and is small and light enough that a single person can haul it into and out of the water.

Oakes wouldn’t say what the robots cost, but said they were in the “five figures” whereas a similar commercial device could run $1 million or more.

His business plan is to offer “robots as a service” in which Reefgen will bring its devices and experts to locations where partner organizations like DNR, the U.S. Navy, departments of transportation and others need help with restorations. There’s potential for demand in Europe following approval of a mandate requiring EU states to restore 20% of their degraded lands and waters by 2030 — which in places will include seagrass beds.

The project in south Puget Sound is just a demonstration for now, but the team this week revisited spikes planted in July that were securely in place and the eelgrass appeared healthy.

DNR’s Franz was excited about the robot’s potential.

As Reefgen improves its system, “it’ll actually be cheaper in the end to get more restoration,” she said. Without technology like this, she added, “the manpower, it would take a huge amount.”

Keep scrolling for additional photos.