AI Dreams: Microsoft @ 50, Chapter 1

[Editor’s Note: Microsoft @ 50 is a year-long GeekWire project exploring the tech giant’s past, present and future, recognizing its 50th anniversary in 2025. Starting today and in the months ahead, we’ll revisit some of Microsoft’s biggest milestones, missteps, and turning points to understand the company’s journey to this point, and what’s next.]

It was a research paper that inspired a multi-billion dollar bet.

With a title only an AI scientist could love, “A Universal Law of Robustness via Isoperimetry,” the paper by Microsoft’s Sebastien Bubeck and Harvard’s Mark Sellke showed the importance of dramatically boosting the scale of artificial intelligence models, training them with many more parameters than previously imagined.

But more than impressing the chairs of the 2021 Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, the research helped to convince Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and other senior leaders to spend billions more on AI infrastructure.

The investment in data centers and advanced processors provided the backbone to train and deploy massive AI models, not only for Microsoft but for its partner, ChatGPT maker OpenAI, contributing to AI breakthroughs that captured the attention of the world.

It was a “major, major moment in this whole AI journey,” said Peter Lee, the Microsoft Research president. “For me, it’s the poster child of why, not only at Microsoft, but at all the big tech companies, research has suddenly become so important.”

At Microsoft, it was a moment decades in the making.

The story of AI at Microsoft begins even before the company got its start, with the science fiction books that inspired co-founder Paul Allen to dream about a future in which robots and other intelligent machines would complement and assist humans.

Hints of AI are sprinkled throughout the company’s early years. They’re evident in co-founder Bill Gates’ vision for “information at your fingertips,” and in his belief in the potential for computers to see, hear, learn, and make decisions on their own.

Since the early 1990s, the promise of AI has been a driving force behind Microsoft’s research division, which now employs more than 1,100 people with a track record of breakthroughs in speech recognition, computer vision, machine learning, and other research that continues to advance the state of the art in artificial intelligence.

AI has simmered for years in Microsoft’s products. It’s the secret sauce behind Microsoft Exchange spam filters, the Outlook feature that prioritizes emails in your inbox, Word’s ability to detect subtle mistakes in grammar, and the way Windows works behind-the-scenes to predict which app you’ll be using next, to load it faster.

And now it’s starting to boil. The clearest example comes from GitHub, the software development platform acquired by Microsoft in 2018. GitHub Copilot, the AI coding companion, accounted for 40% of GitHub’s revenue growth last year, and is now a larger business on its own than all of GitHub was when Microsoft bought it.

AI was responsible for 9 percentage points of the 33% increase in Microsoft’s Azure and cloud services revenue in its most recent fiscal year, translating into hundreds of millions of dollars in additional revenue for the company.

Microsoft’s shares are up more than 80% in the past two years, largely fueled by the potential that investors see for AI to drive future growth in the company’s business.

But many of these early examples are low-hanging fruit, benefitting in part from being early to market. Things are getting tougher as Microsoft expands AI across its product lines. The Information reported in September that some enterprise customers weren’t yet seeing enough benefit from Microsoft 365 Copilot, the AI productivity assistant, to justify the extra cost of $30/user per month.

The competition is also getting stiffer, from an array of heavily funded startups, plus longtime rivals such as Google, Amazon, and Salesforce — whose CEO Marc Benioff has singled Microsoft out, saying its AI has disappointed business customers.

Microsoft was early in seeking to address AI safety issues, including the formation of its AI and ethics in engineering and research (Aether) committee in 2016, long before the boom in generative AI. Privacy and security issues nonetheless delayed the release of the flagship AI feature, Recall, for the new Copilot+ PCs this year.

Meanwhile, the extraordinary amounts of power needed to train and run foundation models are making it even more difficult for Microsoft and other companies to reach their already ambitious goals for sustainability and the environment.

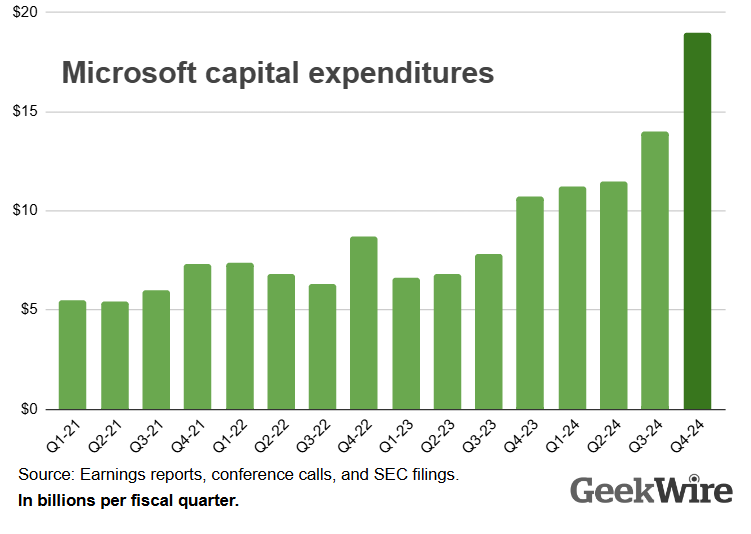

Microsoft isn’t backing down. The company reported a record $19 billion in capital spending in the June 2024 quarter alone, largely to support its long-term AI and cloud infrastructure, which includes its own specialized processors for training and running AI models. Amy Hood, the company’s chief financial officer, told analysts to expect capital expenses to go up even more in the coming years.

Just as the PC and cloud defined Microsoft’s first 50 years, and just as its struggles in mobile set the company back in the smartphone era, its success or failure in AI promises to determine its fate for decades to come.

For this first installment in our Microsoft @ 50 series, GeekWire spent more than a month digging into the company’s work in AI; interviewing key Microsoft insiders, past and present; and revisiting the historical archives, including our own reporting on the company as journalists in Seattle for more than two decades.

‘A utility belt for human cognition’

“There’s so much potential with AI for the dream of what Microsoft was created to be doing,” said longtime Microsoft research leader and AI specialist Eric Horvitz, who is now the company’s chief scientific officer. “Computing is an incredibly empowering force for the planet, for empowering people to do new things.”

Microsoft’s first mission — a computer on every desk and in every home (running Microsoft software) — has become a more amorphous yet ambitious pursuit: “to empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more.”

AI fits perfectly with this, as Horvitz sees it: It’s “a utility belt for human cognition.”

Horvitz has been pursuing this potential at Microsoft for more than three decades. After receiving his Ph.D and M.D. from Stanford, he was working with colleagues on a startup in the early 1990s focused on early forms of AI for medicine.

He remembers Microsoft’s chief technology officer at the time convincing him to join the company with quite possibly the nerdiest recruiting pitch ever — playing on Horvitz’s devotion back then to Bayesian Networks, graphical AI models that predated the deep neural networks that have fueled the recent generative AI boom.

“My turning point was where Nathan Myhrvold leaned into me, in his passionate recruitment, and said, ‘Bill Gates is a Bayesian, and he really wants your stuff to be in everything we do.’ I said, really? OK, well, I could see an opportunity there.”

Microsoft acquired Horvitz’s startup in 1992, bringing him to its fledgling campus in Redmond, Wash., with his colleagues Jack Breese and David Heckerman.

But before the AI revolution could begin, he learned, a company’s gotta pay the bills.

“I think many people at Microsoft didn’t share our passion, and were mostly interested in getting the plumbing right — which is a really good thing to do,” Horvitz said. “When I first got to Microsoft, I think one of my earliest patents was generalized cut-and-paste. … ‘I can cut from an Excel spreadsheet and paste it into a document!’ That was something that was patentable and interesting.”

Part of the challenge was the phenomenon known as an “AI winter,” broader industry cycles in which technological setbacks and disillusionment about the rate of AI progress resulted in decreased funding and waning interest across the field.

The original Microsoft Research Plan, authored by Myhrvold in 1991, cited natural language processing as one of the areas the new research group might explore, but didn’t delve into the larger possibilities of AI as a technology.

“I was interested in AI back then, but my enthusiasm was tempered by these crazy cycles of boom and bust,” Myhrvold explained in a recent interview. “It’s never a good way to run a research thing, where you say, ‘Ah yes, we had a big blossoming, and then we fired all those guys, and now we want to get back to it again.’ ”

In The Road Ahead, the 1995 book written by Gates with Myhrvold and Peter Rinearson, the Microsoft co-founder noted that computer scientists had been studying artificial intelligence for decades at that point, trying to develop “a computer with human understanding and common sense.”

But Gates was pessimistic about the timeline: “Although I believe that eventually there will be programs that recreate some elements of human intelligence, it is very unlikely to happen in my lifetime,” he wrote in the book at the time.

Rick Rashid, the longtime Microsoft Research chief, remembers periods when researchers would strategically avoid the term “AI” in proposals seeking outside funding, avoiding the stigma by opting for terms like “machine intelligence.”

But there were signs, even then, of what was to come.

Avoiding a Kodak moment

One example was a project in the 1990s by then-Microsoft researcher John W. Miller, who used a licensed database of Wall Street Journal archives to create a statistical model that could predict the next character in a sentence. It was similar in concept to today’s generative AI models, but on a considerably smaller scale, and without the benefit of the immense computational resources available now.

“Statistical analysis, inferencing, and decision-making were all key tenets of what, in those days, was core AI,” Rashid said. “We were making those investments very early.”

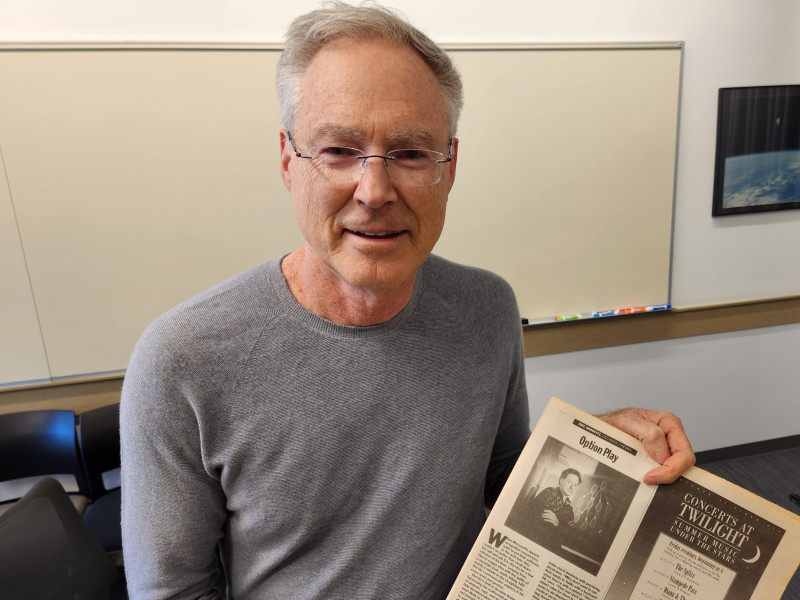

A 1996 profile in the local newspaper Eastsideweek, part of a larger series about Microsoft Research, described Horvitz as a specialist in decision theory, noting the contributions of his research to a Microsoft CD-ROM product at the time. “Pregnancy and Child Care is not just Dr. Spock on a disc,” journalist Roger Downey wrote. “It allows the user to identify an area of concern, then poses a series of questions, the answer to each determining the next, until a tentative diagnosis is reached.”

Microsoft “has already put decision theory to work in its Office product line,” the Eastsideweek piece noted. “It hides in the background while keeping track of the user’s activity, ready to pop up with pertinent advice when problems come up.”

Sound familiar? “Clippy” the Microsoft Office assistant — aka “the little paperclip with the soulful eyes and the Groucho eyebrows” — debuted later that year with the release of Office 97, going on to interrupt the drafting of untold numbers of term papers and letters at inconvenient moments before its official retirement in 2001.

Years after that, some leaders of the Office team weren’t keen on revisiting that era.

Around 2008, Horvitz was participating in an internal review about what was happening with AI in Microsoft Office. He remembers Paul Allen, the Microsoft co-founder, being in the room, making a special visit that day. Gates had announced his plans to retire from Microsoft, and was approaching the end of his day-to-day role at the company. Steve Ballmer, then Microsoft’s CEO, was also there.

At one point during the meeting, Gates asked someone on the Office team, “What about AI?” As Horvitz recalls, the response was, “Well, AI doesn’t really work.”

Horvitz, who was president of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence that year, felt compelled to say something. He stood up and told everyone in the room, “We don’t want to be in a boardroom that sounds like the boardroom at Kodak when somebody said, ‘Digital cameras? Yeah, but they don’t really work.’ ”

In pursuit of ‘Impossible Things’

Rashid, a computer scientist known for his pioneering work in areas including operating systems and computer vision, was recruited by Myhrvold from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh to found Microsoft Research in 1991. After initially turning down the job, he was convinced to move to Seattle through a recruiting effort that included Myhrvold sending Ken Griffey Jr. merchandise to Rashid’s kids.

Rashid, who went on to run Microsoft Research for 22 years, wrote an internal memo in March 2010 challenging the company’s researchers with what he dubbed the “Impossible Things Initiative.” It was named after the queen’s comment in Alice in Wonderland about believing “as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

The first Impossible Thing: a universal speech-to-speech language translator.

After more than two years of development, in October 2012, Rashid stunned a crowd in Tianjin, China, with a Microsoft Research system that automatically translated his spoken words from English into computer-generated Mandarin, in his own voice.

The key technological ingredient: deep neural networks, an early form of the approach that would spark the generative AI revolution a decade later.

A catalyzing moment for AI

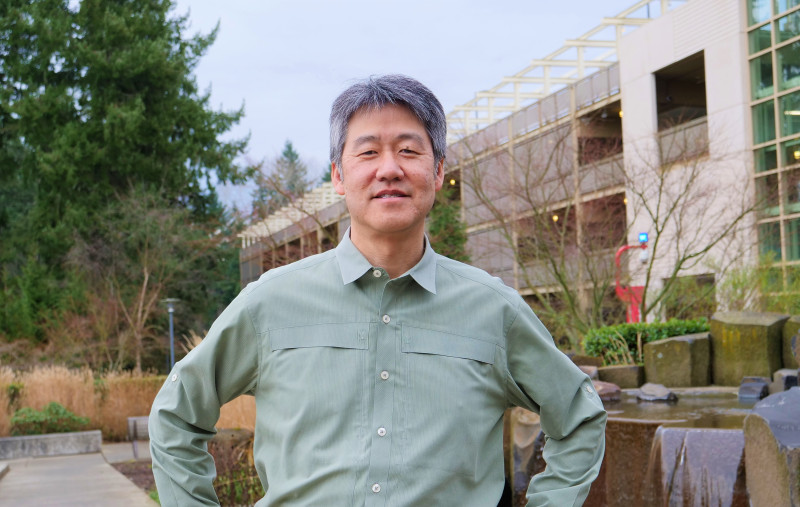

When Lee, the current Microsoft Research president, joined the company in 2010 to lead its Redmond lab, he was initially skeptical of a project that used neural networks for speech recognition. During his long tenure at CMU, starting in 1987, Lee had seen researchers struggle with this approach, including a professor named Geoffrey Hinton.

Lee wasn’t an expert in speech recognition, but he knew enough to be skeptical. Common wisdom at the time was that the most promising approaches weren’t neural networks but rather Hidden Markov Models or Gaussian Mixture Models, both of which use clever math to find patterns in complex, uncertain data.

Neural networks, in contrast, are inspired by the structure and function of the human brain, designed to recognize patterns, make decisions, and learn from data.

Upon Lee’s arrival in Redmond in 2010, he learned that Hinton and another academic researcher, Andrew Ng of Stanford, were collaborating with Microsoft’s Li Deng and Alex Acero to use layers of neural networks for speech recognition.

“And so I look at this project, and I get briefed, and in my head, I think, ‘Wow, this is really ridiculous,’” Lee recalled in a recent interview.

But he soon realized it wasn’t ridiculous at all. Contrary to his hypothesis, in the months that followed, this layered approach to neural networks led to dramatic improvements and reductions in error rates in speech recognition.

Ng went on to further advance the field as a founder of Google Brain. A serial AI startup founder, he was named to the Amazon board earlier this year. Hinton joined Google, too, before leaving last year, citing concerns about the dangers of AI. His name may sound familiar: Last week, he was awarded the Nobel Prize.

At Microsoft, by the end of 2011, much of the focus of the company’s AI research had shifted to neural networks. After Nadella became CEO in 2014, one of the first research demonstrations he saw was a neural speech-to-speech translator, and he quickly gave the go-ahead to roll the technology out as a feature in Skype.

Things snowballed in the years that followed, with progress emerging from teams inside Microsoft, Google, OpenAI, the Allen Institute for AI and others.

Key advances included the advent of transformers, a powerful technique that helps AI understand language by focusing on the most important parts of a sentence; and self-supervised learning, in which AI teaches itself using massive amounts of data.

In 2017, five years before ChatGPT became a household name, Microsoft created an AI and Research group as a new engineering division, alongside the Office, Windows and Cloud & Enterprise divisions, expanding it to 8,000 people within a year of its creation.

“We’ve had this dream for a long time — that systems could be smarter and model the way you think,” said Lili Cheng, a longtime Microsoft research and engineering leader, in an interview with GeekWire at the time.

Throughout these years, AI was a recurring theme at Microsoft Research’s annual TechFest event, where product teams were exposed to the latest projects from the company’s labs; and in annual gatherings held by Craig Mundie, Microsoft’s longtime research and strategy chief, with tech reporters on the Redmond campus.

And along the way, Microsoft researchers continued to make steady progress in the field, reaching new milestones in speech recognition, computer vision, machine learning, AI models, and other breakthroughs to enable more human-like machines.

But by mid-2019, Microsoft CTO Kevin Scott was concerned that the company was getting caught flat-footed. On the morning of June 12, 2019, he sent an email to Gates and Nadella that would quickly open up a new horizon for the company.

‘Very, very worried’

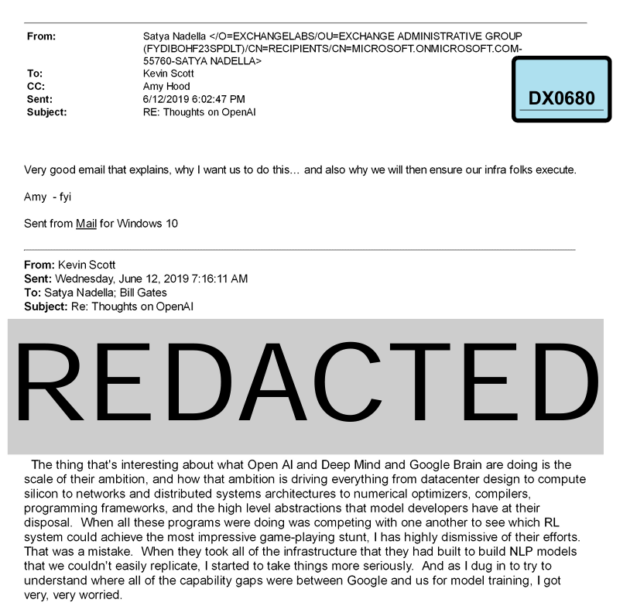

In that email, with the subject line, “Thoughts on Open AI,” Scott acknowledged that he had underestimated the company’s rivals in AI — singling out Open AI, DeepMind and Google Brain for “the scale of their ambition.”

That outsized ambition, he wrote, was giving Microsoft’s competitors powerful new tools to create breakthrough AI models, including data center designs, sophisticated computing infrastructure, and core development technologies.

Alluding to DeepMind and other AI systems that defeated top human players in games such as Go and chess, Scott wrote that he had been “highly dismissive” of these efforts when they seemed more about achieving “the most impressive game-playing stunt.”

“That was a mistake,” Scott admitted to Microsoft’s current and original CEO.

When other companies started to use that same infrastructure to build natural-language processing models that Microsoft couldn’t easily replicate, “I started to take things more seriously,” he wrote. “And as I dug in to try to understand where all of the capability gaps were between Google and us for model training, I got very, very worried.”

As one of Microsoft’s biggest rivals in the cloud and productivity applications, the prospect of Google achieving a big lead in AI was a good reason for concern, given the potential for the search giant to further chip away at Microsoft’s core businesses.

Scott sent the message to Gates and Nadella the morning of Wednesday, June 12, 2019, according to a heavily redacted version of the email made public during Google’s U.S. antitrust trial this year.

Nadella forwarded it that evening to Hood, the Microsoft CFO, adding the note, “Very good email that explains, why I want us to do this… and also why we will then ensure our [infrastructure] folks execute.”

A little more than a month later, Microsoft announced its first $1 billion investment in OpenAI, promising to build “a computational platform in Azure of unprecedented scale” to train and run advanced AI models.

That was just the start. Microsoft increased its total investment in OpenAI to more than $10 billion in 2023. After weathering the temporary ouster of OpenAI CEO Sam Altman last year, Microsoft upped its investment again by participating in OpenAI’s recent $6.6 billion funding round.

Horvitz, Microsoft’s chief scientific officer, was in one of the first meetings where Microsoft and OpenAI’s technical leaders discussed a possible collaboration.

He recalled being surprised as Ilya Sutskever, the OpenAI co-founder who was its chief scientist at the time, stood at the whiteboard with a marker to sketch out for the Microsoft team how OpenAI was going to build artificial general intelligence, a theoretical future form of AI that would match or surpass human cognition.

It was clear that OpenAI was “quite a different kind of company,” one that was “a little bit more out of the box, trying to do things that maybe were unrealistic, and not as scientifically based,” Horvitz said.

Microsoft researchers have always been ambitious in AI, with plenty of “wild ideas” of their own, Horvitz said.

“But when it came to machine learning, we hadn’t fully grokked yet the power of the scale,” he said. “We hadn’t really thought deeply about [the fact that] it’s just going to be essentially the same patterns, but with more data, more computation.”

‘Earth got this amazing thing’

Given the decades of work and progress on AI inside Microsoft over the years, how was it received internally when the company entered into the OpenAI partnership?

“Whenever there’s been an acquisition at the company … or any kind of partnership, there’s always been a question about, ‘Well, why not us? Did we do enough? How did that happen?” Horvitz acknowledged. “The question would come up. It’s very natural.”

But the reality is that Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and other top tech companies have been investing in AI for decades, and it’s the nature of the technology world that a startup would emerge out of nowhere and surprise everyone with a different approach, said Oren Etzioni, the longtime Seattle-based artificial intelligence leader.

“I view that whole story as a huge compliment to Microsoft, because a lot of companies would suffer from NIH, as it’s called — ‘not invented here’ — and would not have the flexibility and the boldness to execute against that. It would be too much,” said Etzioni, who previously ran the Allen Institute for AI, started by the late Microsoft co-founder.

Rather than faulting Microsoft for not going it alone, credit the company for having the resources, insight, and guts to make a multi-billion dollar bet on OpenAI, agreed Myhrvold, who since his tenure as Microsoft’s CTO (and tenacious recruiter of research leaders) has gone on to a multifaceted career in a variety of scientific, technical, and creative, and culinary fields, co-founding and leading the firm Intellectual Ventures.

“There’s always people in an organization that view dealing with an outside firm as disenfranchising them. ‘Why don’t you give me that $10 billion and see what we do with it?’ And it will be a perfectly rational thing to argue,” Myhrvold said.

“And yet their conclusion was, ‘No, we have to go for this.’ And because they had that conclusion, Earth got this amazing thing … because once you’ve shown it can be done, that has now channeled billions more into all of these competitors of OpenAI. The rate of progress will go way up. I think it’s great. This is just a terrific thing for humanity.”

But given the partnerships with OpenAI and others — including the Inflection AI deal that saw the startup’s co-founder Mustafa Suleyman become CEO of Microsoft AI — one risk is the potential for Microsoft’s homegrown AI talent to go elsewhere.

Longtime Microsoft followers have taken note of high-profile AI departures in recent years, such as speech recognition pioneer Xuedong (XD) Huang, former Microsoft technical fellow and Azure AI chief technology officer, who’s now CTO at Zoom.

Just this week, the news emerged that Sebastien Bubeck, the Microsoft researcher who led the pivotal research into AI model robustness, is joining OpenAI.

Is there a risk that Microsoft is effectively outsourcing long-term AI research to OpenAI? In a statement addressing that question, the company said it doesn’t see one — citing its long history and ongoing work at the forefront of AI research and applications.

The company pointed to its continued efforts to make AI models better, faster, cheaper and more capable, while focusing on responsibility and security, and developing advanced hardware and infrastructure for training and running AI models.

Examples include Microsoft’s development of the breakthrough Megatron-Turing Natural Language Generation model, and the more recent Phi-3 and Phi-3.5 family of small open models, which the company says outperform models of similar and larger sizes.

In addition, the company said, Microsoft Research is exploring alternative AI architectures and multi-modal models, seeking to apply AI in new ways.

Others look at this and ask if Microsoft is going overboard on AI.

“I think the biggest risk right now, at least in my view, is they’re so focused on AI at Microsoft right now, they’re ignoring a lot of other things that they should be paying attention to,” said Mary Jo Foley, editor-in-chief at the Directions on Microsoft research firm, who has covered the company for most of her 35 years as a journalist.

At times, she said, Microsoft seems to have glossed over the security and compliance issues, and the fundamental work that needs to be done under a data estate before AI can be effectively implemented. Meanwhile, many big enterprise customers are more interested in more basic improvements in Windows Server, Azure, and Office.

“That’s what normal businesses care about. And I feel like that stuff has taken a complete back seat to all the AI hype,” Foley said. “I think that’s more worrisome than anything. If Microsoft bets wrong here, and this becomes another Web3 or Windows Phone, what are they going to do?”

‘From impossible to merely difficult’

But for many inside Microsoft, the AI dreams are fast becoming reality.

Just as cloud computing fundamentally changed technology research, shifting workloads and projects from on-site servers to remote data centers, the field is now becoming “AI native” in an even bigger way, Lee said.

He cited the example of a new Microsoft software engineering research lab in Redmond, called the Foundations of Scalable Software Engineering. It’s relying heavily on generative AI to synthesize elements of its research that would have normally relied on traditional theorem proving, deep program analysis, and machine simulation.

“It’s just really profoundly different in that way,” he said. “And so that’s just happening across the board … not just at MSR, but I think everywhere, really.”

For Microsoft’s product teams, and the developers who build on the company’s platforms, the challenge now is to leverage AI advances to create real value for users.

Scott, the Microsoft CTO, appeared on stage with OpenAI’s Altman this year at the Microsoft Build conference in Seattle, characterizing recent developments in AI as the dawn of a new era, and a whole new opportunity for software developers.

The best way to create breakthroughs now, Scott told the crowd, is “to focus on things that have made the transition from impossible to merely difficult.”

Fifty years earlier, a similar realization — that the previously impossible was suddenly merely difficult — made Paul Allen grab a Popular Electronics magazine off the shelf at a Harvard Square newsstand, and go looking for his childhood buddy from Seattle.

Coming next month: How Microsoft’s founding duo set the course for its future.